Over the last several years, many studies have pointed to the significance of the brain-gut connection in neuropsychiatric disorders and mood. Compared with healthy people, patients with this clinical presentation possess significant differences in the variety and composition of the gut microbiota, where certain bacteria found in the digestive tract have been connected to inflammatory markers, metabolic profiles, intensity and duration of illness, and psychological problems.

Brain-Gut-Microbiota Axis

The digestive system of a human being is home to around 100 trillion different kinds of microorganisms (most of them bacteria, but also viruses, fungi, and protozoa).

Dysbiosis (imbalance) in the gut microbiota is shown to be related to a wide variety of systemic disorders, including functional bowel disorders, inflammatory disease, atherosclerosis, metabolic disease, and neuropsychiatric disorders. Additionally, growing evidence suggests that the microbiome may affect and moderate emotional behaviour.

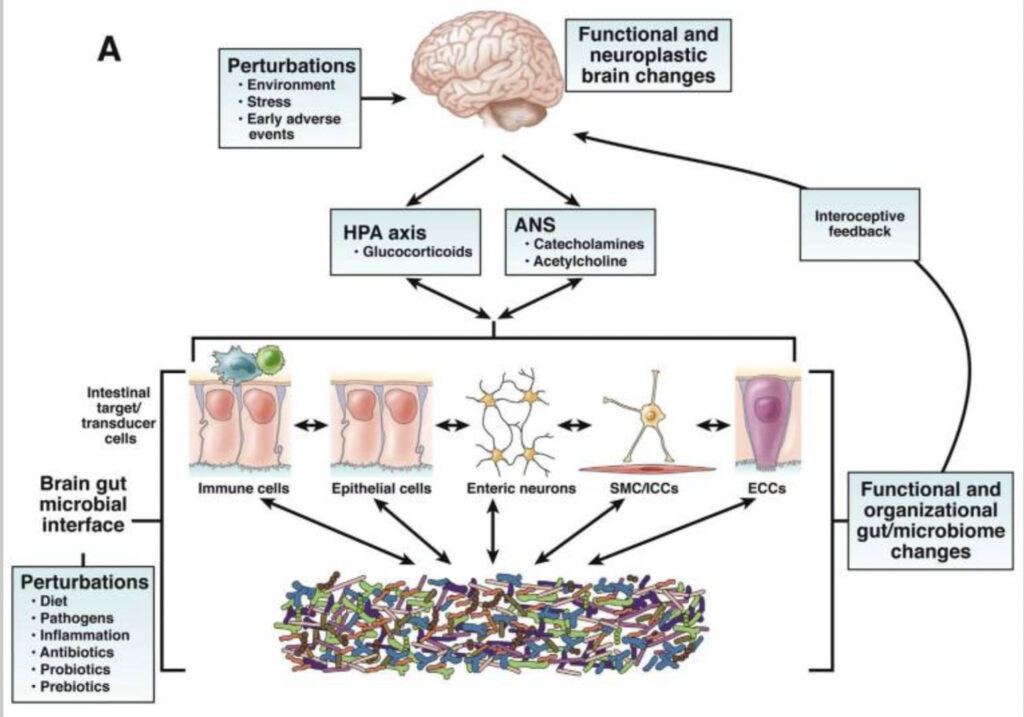

The relationship between the microbiota in our gut and the brain is a two-way track; this implies that the gut microbiota influence brain growth and function, and the brain, in turn, interacts with the gut microbiota via the neuroimmune, neuroendocrine, and neurological systems. This communication between the brain and the gut microbiota is referred to as the brain-gut-microbiota axis. The system includes not only anatomical channels, but also hormonal, humeral, metabolic, and immune system paths. Through this two-way communication system, signals sent from the brain may impact the physiological processes that occur in the gastrointestinal tract, such as motility, secretion, and immunological function. Likewise, signals sent from the gastrointestinal tract can affect the brain’s capacity to regulate reflexes and mood.

Microbiota and Mood

Studies investigating the mechanisms of action that gut bacteria have on the cognitive and emotional centres of the brain, both directly and indirectly, reveal that changes in the composition of the microbiota are linked to corresponding shifts in the brain’s communication networks. Mood disorders, autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, and Parkinson’s disease are only some of the neuropsychiatric conditions that have been associated with changes in gut microbiota composition.

Many individuals with gastrointestinal distress have a higher likelihood of suffering from mental disorders as well. Demonstrating this connection, Palsson and Whitehead (2002) found that patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) who were treated with psychiatric medications had a substantial reduction in the severity of their gastrointestinal symptoms. Another study revealed that patients who suffered from depression had an abnormal gut microbiota composition, linked to anomalies in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, low-grade intestinal inflammation, and an unbalanced neurotransmitter metabolism through the brain-gut-microbiota axis. Abnormalities in intestinal permeability are considered to be the root cause of the persistent low-grade inflammation that may be present in stress-related mental diseases. Furthermore, individuals who are experiencing symptoms of depression usually demonstrate elevated production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1, IL-6, tumour necrosis factor, interferon-gamma, and C-reactive protein. These markers can be measured in the blood.

Beneficial metabolites, in particular SCFAs, inhibit the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines such as NF-B, whereas the gut microbiota affects the transcription of the same cytokines, with dysbiosis setting off the so-called inflammasome pathway. Thus, gut microbial imbalance may lead to the pathogenesis of mental diseases, which supports the idea that the pathogenic process involves bidirectional communication between the stomach and the brain.

Nutritional Interventions to Modulate Gut Microbiome

Several factors may affect the gut microbiota, including genetics, age, gender, environment, stress, drugs, probiotics and prebiotics, and psychosocial problems. However, among the many factors that have an impact, food is one of the most critical.

Recent research has shown that the impact of nutrition on the gut microbiota and long-term health consequences may be more important than host genetics in certain cases.

Healthy eating patterns that include a sufficient amount of fruits and vegetables, a rich supply of dietary fibre, healthy fats (MUFAs and PUFAs), and an emphasis on plant-derived proteins should help support gut microbiota variety and functioning, allowing the gut microbiome to serve its host efficiently.

Dietary treatments aimed at changing the gut microbiota should concentrate not only on macronutrients (this refers to ratios of fat, carbs, and protein), but also on micronutrients (vitamins, minerals, and trace elements), as well as both prebiotics and probiotics.

However, resolving issues with the microbiome might not be as straight forward as increasing veggie and fibre intake and eating healthily. It’s important to look at each individual’s unique circumstances.

Many different dietary models might be useful in modulating the microbiome, such as the FODMAP diet or the Mediterranean diet. On the other hand, the dietary strategy must be personalised to each person’s requirements. For instance, some kinds of fibre and carbs may trigger irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). As a result, developing a dietary plan that accommodates such specific demands while continuing to nourish the microbiome is vital.

clinical applications

In my clinical practice, I take a comprehensive clinical history of each client to understand their symptoms and start mapping potential root causes. Based on this initial assessment, I might, if relevant, recommend functional testing to inform my initial clinical hypothesis and treatment plan. Functional testing can vary from microbiome analysis (often by stool test) to carrying out additional tests to discover any nutritional shortages (e.g., blood tests). Based on all these inputs, I then develop a detailed, customised nutritional and lifestyle approach tailored to the individual client.

References

How to Avoid Holiday Food Stress: My Top 5 Methods

How to Avoid Holiday Food Stress: My Top 5 Methods

Leave a Reply